Thesaurus Mediaevalis

The goal of this book series, published by Martin Opitz Publisher, is the categorisation and historical evaluation of the stone carvings linked to the most significant buildings of the medieval Hungarian Kingdom.

Publications

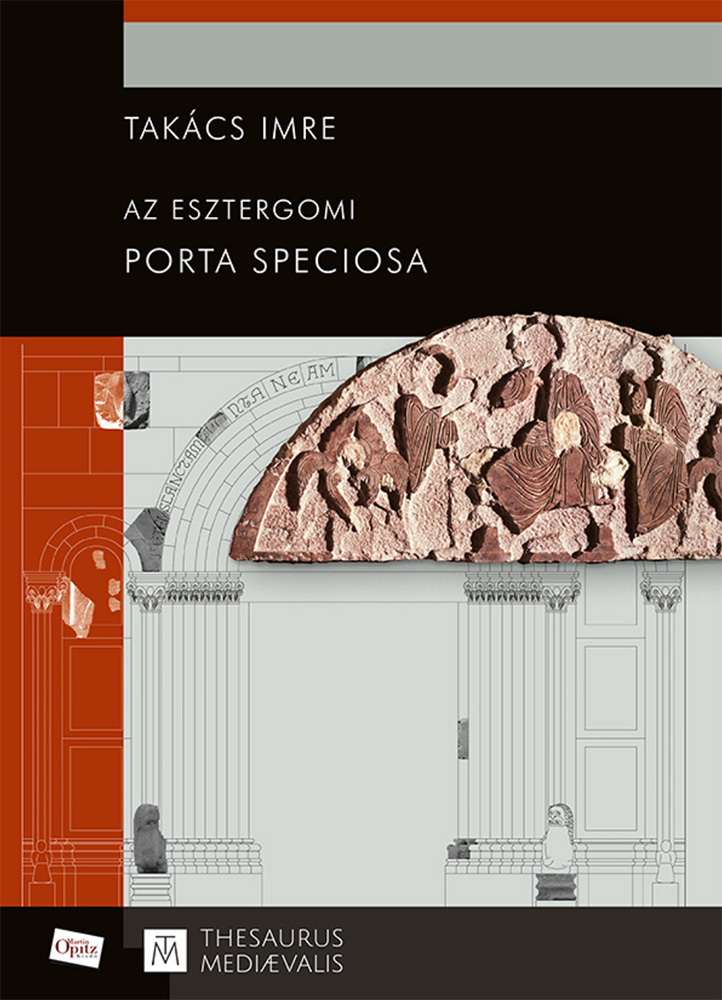

Takács Imre

The Porta Speciosa in Esztergom. One of the most intricate, although least accessible object of the era of the Árpáds have been keeping art historians occupied for more than a hundred years. This publication, in the frame of a new research program supported by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, is centered around this outstanding monument: the former main gate of the Basilica of Esztergom, complete with marble ornaments and statues. The Porta Speciosa was built at the end of the 12th century, under the reign of King Béla III, and although it survived the turmoil of the period of the Ottoman occupation, it exists only in pictures and minuscule fragments since the building of the new cathedral in the 19th century. The starting point of the research was the collection and categorization of these fragments, and ended with the publication of a study regarding the structure of this work of exceptional quality, as well as the artistic leanings of its creators and the substance of its figural ornaments. What were the predecessors of its structure? Which European artistic centers can be connected to these fragments? How did the artist arrive to the Hungarian Kingdom? What can we learn about their sources and the demands of the commissioner based on the style of their work? Were there any pauses, restarts or changes in plans during the work? The study seeks answers to these questions.

Takács Imre

The Porta Speciosa in Esztergom. One of the most intricate, although least accessible object of the era of the Árpáds have been keeping art historians occupied for more than a hundred years. This publication, in the frame of a new research program supported by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, is centered around this outstanding monument: the former main gate of the Basilica of Esztergom, complete with marble ornaments and statues. The Porta Speciosa was built at the end of the 12th century, under the reign of King Béla III, and although it survived the turmoil of the period of the Ottoman occupation, it exists only in pictures and minuscule fragments since the building of the new cathedral in the 19th century. The starting point of the research was the collection and categorization of these fragments, and ended with the publication of a study regarding the structure of this work of exceptional quality, as well as the artistic leanings of its creators and the substance of its figural ornaments. What were the predecessors of its structure? Which European artistic centers can be connected to these fragments? How did the artist arrive to the Hungarian Kingdom? What can we learn about their sources and the demands of the commissioner based on the style of their work? Were there any pauses, restarts or changes in plans during the work? The study seeks answers to these questions.

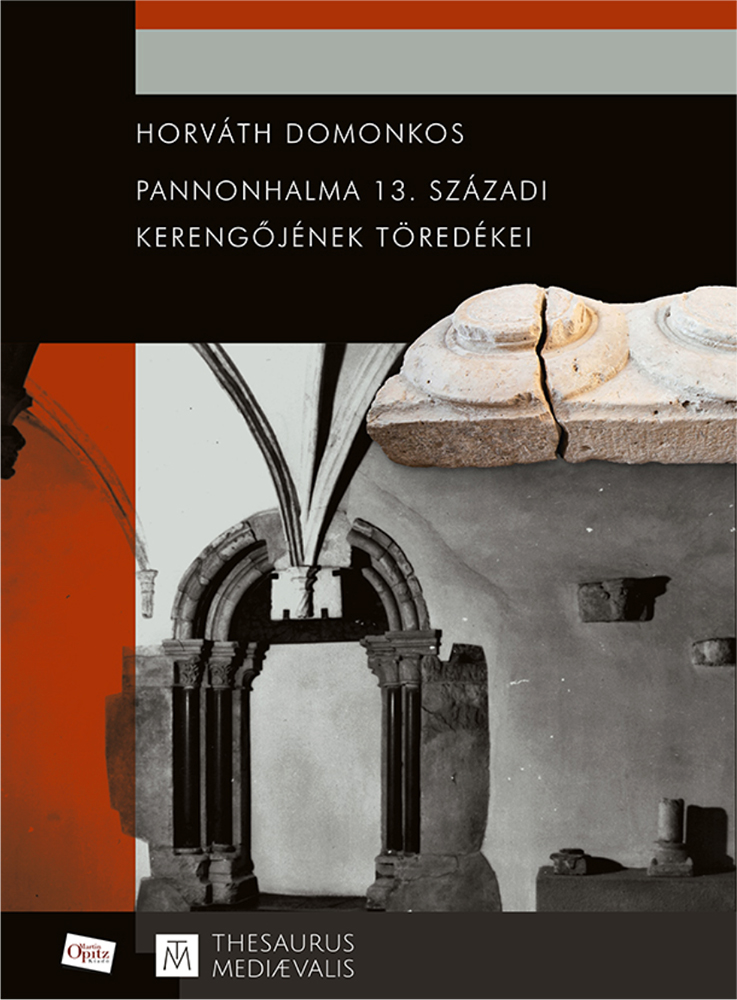

Horváth Domonkos

A pannonhalmi bencés apátság kitűntetett helyzetét nem csak egyedi egyházi státuszának, kiemelkedő apátjainak, de az építkezés izgalmas és sok kérdést felvető történetének is köszönheti. A művészettörténeti kutatás új eredményeket hozott a 13. századi apátsági templom faragványainak datálását és műhelykapcsolatait illetően. Jelen tanulmány a friss eredményekre, illetve a fennmaradt töredékekre és régészeti feltárásra támaszkodva kísérli meg az eddig keveset kutatott pannonhalmi 13. századi kerengőnek a vizsgálatát és értelmezését.

A kerengők funkcionálisan és szimbolikusan egyaránt központi szerepet töltöttek be a szerzetesi életben. Mint építészeti terek a 13. század elejétől jelentek meg rendszeresen az apátsági épületekben. A tanulmányban nyomon követhetjük a kerengőépítészet kialakulásának korai példáit a Magyar Királyság és Ausztria területeiről, számos példán keresztül helyezve el benne Pannonhalma első kerengőjét.

Horváth Domonkos

A pannonhalmi bencés apátság kitűntetett helyzetét nem csak egyedi egyházi státuszának, kiemelkedő apátjainak, de az építkezés izgalmas és sok kérdést felvető történetének is köszönheti. A művészettörténeti kutatás új eredményeket hozott a 13. századi apátsági templom faragványainak datálását és műhelykapcsolatait illetően. Jelen tanulmány a friss eredményekre, illetve a fennmaradt töredékekre és régészeti feltárásra támaszkodva kísérli meg az eddig keveset kutatott pannonhalmi 13. századi kerengőnek a vizsgálatát és értelmezését.

A kerengők funkcionálisan és szimbolikusan egyaránt központi szerepet töltöttek be a szerzetesi életben. Mint építészeti terek a 13. század elejétől jelentek meg rendszeresen az apátsági épületekben. A tanulmányban nyomon követhetjük a kerengőépítészet kialakulásának korai példáit a Magyar Királyság és Ausztria területeiről, számos példán keresztül helyezve el benne Pannonhalma első kerengőjét.

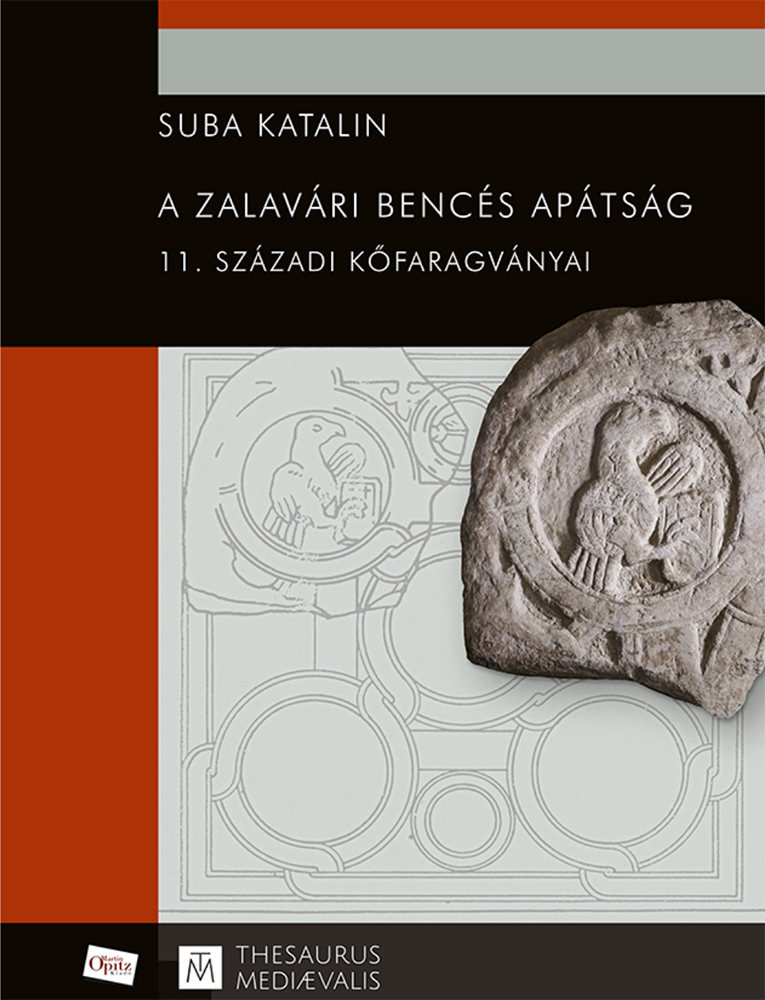

Suba Katalin

11th-century stone carvings from the Benedictine Abbey of Zalavár. Researches on the art of the 11th-century Hungarian Kingdom are often burdened with hypotheses due to the large-scale decay of the buildings and artefacts and the lack of contemporary written sources. The only existing pictorial representation of the Abbey of Zalavár is a drawing from a 16th-century topographic survey, showing the fortifications of the area. The fort itself was demolished by a detonation in 1702 and its remaining stones have been later used up in various constructions. However, the recovery of the original building is still not impossible, since stone carvings found in the area can provide us an idea of the former church. These fragments have been considered to be the oldest surviving monuments of the Christianized Hungary by the art-historical discourse, their evaluation therefore contributes not only to our knowledge about the church of St. Adrian in Zalavár, but also to the methods of stonemasonry in the era of the foundation of the state, as well as to questions regarding the liturgical furnishings of our earliest churches.

Suba Katalin

Researches on the art of the 11th-century Hungarian Kingdom are often burdened with hypotheses due to the large-scale decay of the buildings and artefacts and the lack of contemporary written sources. The only existing pictorial representation of the Abbey of Zalavár is a drawing from a 16th-century topographic survey, showing the fortifications of the area. The fort itself was demolished by a detonation in 1702 and its remaining stones have been later used up in various constructions. However, the recovery of the original building is still not impossible, since stone carvings found in the area can provide us an idea of the former church. These fragments have been considered to be the oldest surviving monuments of the Christianized Hungary by the art-historical discourse, their evaluation therefore contributes not only to our knowledge about the church of St. Adrian in Zalavár, but also to the methods of stonemasonry in the era of the foundation of the state, as well as to questions regarding the liturgical furnishings of our earliest churches.

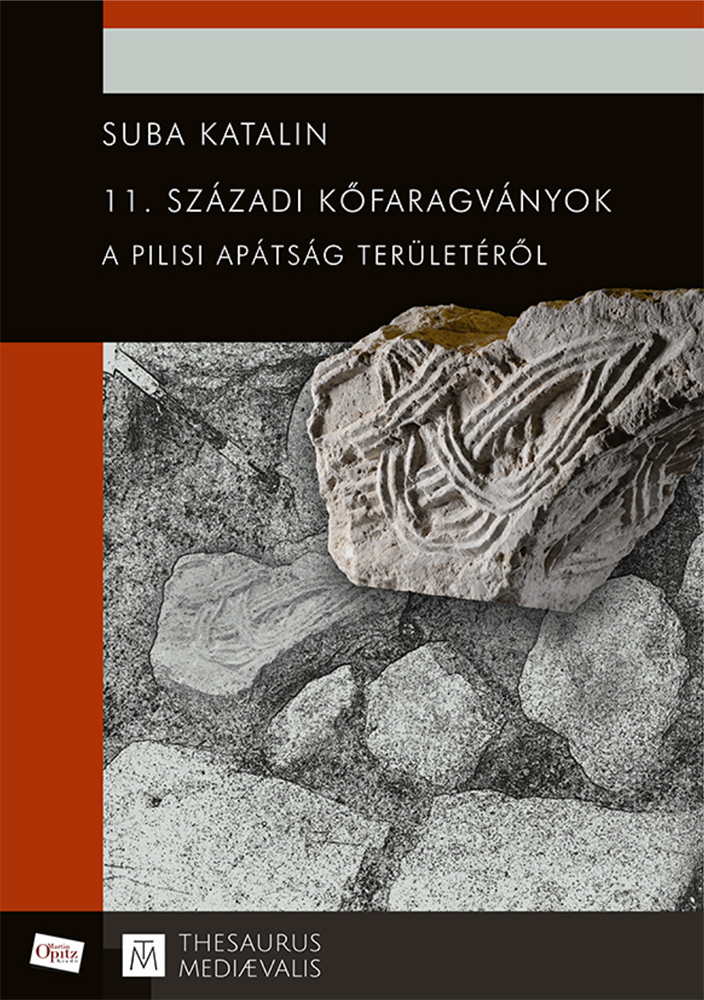

Suba Katalin

11th-century Stone Carvings from the Area of the Pilis Abbey Archaeological research at the area of the Cistercian abbey of Pilis has brought forward several stone carvings that indicated the existence of a much older building complex, including a church. Similar fragments have been collected from the wider area long before this excavation. Based on the style of the fragments, research dates the building to the 11th century. These early stone carvings, especially the ones with palmette ornaments, contribute significantly to our image of the 11th-century architectural ornaments of the Hungarian Kingdom. In this study we attempt to refine our idea of this building complex in Pilis by an art-historical analysis of the fragments and a comparative evaluation of archaeological findings and written sources.

Suba Katalin

Archaeological research at the area of the Cistercian abbey of Pilis has brought forward several stone carvings that indicated the existence of a much older building complex, including a church. Similar fragments have been collected from the wider area long before this excavation. Based on the style of the fragments, research dates the building to the 11th century. These early stone carvings, especially the ones with palmette ornaments, contribute significantly to our image of the 11th-century architectural ornaments of the Hungarian Kingdom. In this study we attempt to refine our idea of this building complex in Pilis by an art-historical analysis of the fragments and a comparative evaluation of archaeological findings and written sources.

Takács Imre (ed.)

The authors of this book dedicate their contributions to an outstanding researcher of medieval art in Hungary and a teacher to several prosperous scientists until his death in 2007: Sándor Tóth. One of the main focus of these studies is to discuss if there is still enough attention, effort and resources to forward studies of the past in an uneasy present, if there are any important and actual topics to research or is there anything left to say in general for the contemporary studies of Hungarian medieval art. Their implied answer is positive without a doubt, although the empty space left behind by this master clearly cannot be filled. As Ernő Marosi has worded in the afterword of this tome: „Sándor Tóth is missing, because his presence was the most important criterium for researching and teaching medieval art in Hungary in the last third of the twentieth century.”

Takács Imre (ed.)

The authors of this book dedicate their contributions to an outstanding researcher of medieval art in Hungary and a teacher to several prosperous scientists until his death in 2007: Sándor Tóth. One of the main focus of these studies is to discuss if there is still enough attention, effort and resources to forward studies of the past in an uneasy present, if there are any important and actual topics to research or is there anything left to say in general for the contemporary studies of Hungarian medieval art. Their implied answer is positive without a doubt, although the empty space left behind by this master clearly cannot be filled. As Ernő Marosi has worded in the afterword of this tome: „Sándor Tóth is missing, because his presence was the most important criterium for researching and teaching medieval art in Hungary in the last third of the twentieth century.”